I took a more stressful position at work three years ago, and I’ve noticed a pattern since then. Whenever I’m on a vacation, my brain works better. My thoughts are clearer, I’m more creative, and I have a broader perspective on what’s happening around me. It’s like a dim light slowly starts to illuminate when I’m away from work, and is fully bright only 3 to 5 days later.

All climbers and athletes understand what happens when you’ve been going too hard for too long. Run, climb, or bike too many days in a row or for too many hours in a day, and you’re going to need to take it easy for a bit. A lot of climbers steal a term from economics to describe this common phenomenon – we call it diminishing returns.

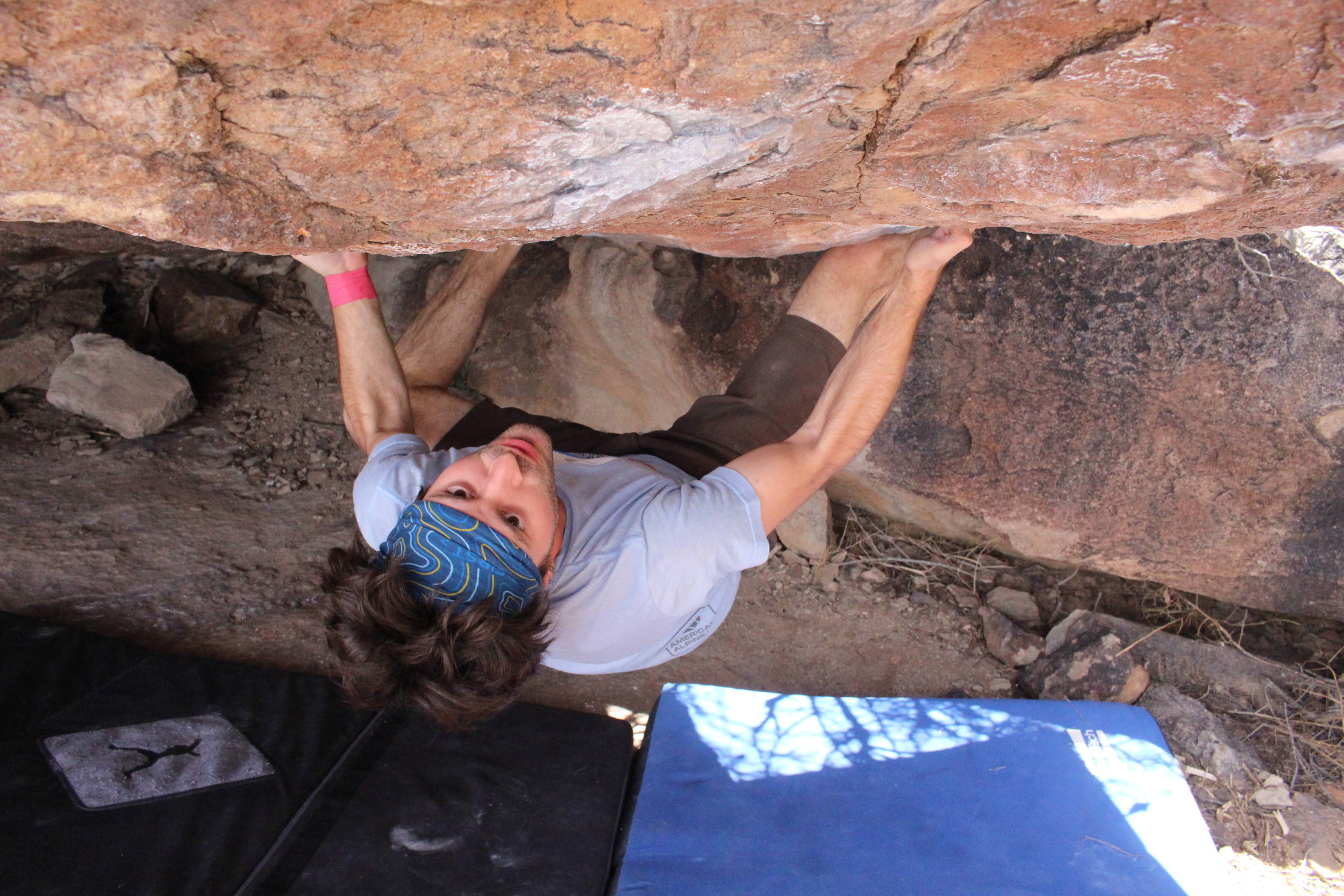

@natalieclimbs showing some serious anxiety

To put it simply, diminishing returns means that when you push your body, you become tired, and the results that you receive from your effort decrease. It’s well understood that when you want to perform at your peak, you need to take some extra rest.

So here’s my question: Why don’t we fully apply this principle to our careers? The typical American work structure is one that allows for very little rest. There aren’t many sports that we could engage in for 40 hours a week, 50 weeks a year without serious physical consequences. So why don’t we expect serious mental consequences from our work structure? From both an employee’s and an employer’s perspective, it seems inefficient to have workers who are constantly battling mental diminishing returns.

Getting your hair perfect is so stressful!!

And while it’s actually quite easy for most of us first-worlders to get physical rest, mental rest is much harder to come by. How could we find space to rest our minds with all of the advertising, social media, and 24-hour news access constantly pervading our brains – not to mention the need to keep up with the responsibilities of our everyday lives. With this in mind, one might wonder why we’re surprised by the amount of mental illness and addiction in our country.

It seems strange that a concept that’s so well understood in the physical world is largely ignored in the mental world. Maybe it’s because we can easily pinpoint physical fatigue, while mental fatigue seems more abstract and vague. Maybe we can more easily connect our physical pain to past events. Maybe our minds just have trouble diagnosing themselves.

No work here, just me and the next hold. Photo: @natalieclimbs

I’m writing this because I get more vacation than my non-teaching friends, so my opportunity to frequently observe these mental losses is fairly unique. So here’s my advice: take a true mental break, take it for more than just a weekend, and take a moment to notice what it’s like to be mentally fresh. If you do, we just might start considering mental returns the same way we do physical returns.

This blog post was inspired and written on a climbing rest day, in the middle of a mental rest week, in Hueco Tanks State Park, Texas. :)